*This post is part of the "Hit Me With Your Best Shot" blogathon at The Film Experience*

**There are spoilers in this post if you haven't seen the film. If that pertains to you, do yourself a favor and check at out as soon as possible. It really is one of the year's best.**

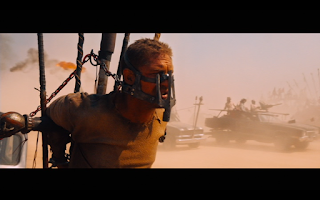

As I wrote in my original review of the film, Mad Max: Fury Road is that rarest of summer anomalies: a film that is massively entertaining, wholly original, and genuinely intelligent, layering a deceptively-simple plot with feminist subtext and then slathering the whole thing in gonzo action sequences that couldn't look more different from, say, Furious 7. The film is the fourth addition to a franchise that has been dormant for 30 years, with a change in lead actor (Tom Hardy taking over for the now-Kryponite Mel Gibson), and the franchise's original director - George Miller - who hasn't headlined a new live-action film since 1998 (Babe: Pig in the City; he directed the two Happy Feet films in the interim).

All of the signs pointed to this being a potential disaster. But if there's one thing Miller can't do, it's make an uninteresting movie - especially when Warner Brothers essentially gave him carte blanche to make the film the way he saw fit. So he made a film that opens with world-establishing narration against a black screen (sorry, you'll have to pay attention to understand; no spelling everything out here), then cuts to our hero, Max Rockatansky (Hardy), with his back to us, looking over the landscape he's surely about to conquer...

**There are spoilers in this post if you haven't seen the film. If that pertains to you, do yourself a favor and check at out as soon as possible. It really is one of the year's best.**

As I wrote in my original review of the film, Mad Max: Fury Road is that rarest of summer anomalies: a film that is massively entertaining, wholly original, and genuinely intelligent, layering a deceptively-simple plot with feminist subtext and then slathering the whole thing in gonzo action sequences that couldn't look more different from, say, Furious 7. The film is the fourth addition to a franchise that has been dormant for 30 years, with a change in lead actor (Tom Hardy taking over for the now-Kryponite Mel Gibson), and the franchise's original director - George Miller - who hasn't headlined a new live-action film since 1998 (Babe: Pig in the City; he directed the two Happy Feet films in the interim).

...only to have him crashed and captured within a few minutes. It's here that the story actually begins.

That story finds Max in captivity at the Citadel, where warlord Immorten Joe (Hugh Keays-Byrne) controls his peoples' water supply, maintains an army of deformed soldiers known as war boys, and keeps several women in slavery to serve either as "breeders" or producers of "mother's milk." However, Max's arrival is complicated when Imperator Furiosa (Charlize Theron) sneaks the breeders out of captivity, kicking off an extended chase through the unforgiving wasteland that will find Max teaming up with Furiosa and attempting to escape war boy Nux (Nicholas Hoult), whom Max is attached to as a human blood bag.

It's all terrific, and it wouldn't be hard to go on and on (and on and on and on...) about the film's stunning visuals and ingenuity. After all, Miller famously utilized practical effects as much as possible, meaning that a lot of those cars you see flipping through the sand are actually blowing up and those guys on poles swaying like metronomes from one vehicle to another are actually doing that. He and cinematographer John Seale (who came out of retirement to do the film) created a world of vibrant oranges and blues, while employing techniques such as changing the frames-per-second rate in certain scenes to give the film a frantic energy. Plus, this is a film in which the chase comes with fan-favorite Doof Warrior, a soldier who's sole purpose is to ride a rig outfitted with massive speakers and shred on a flame-throwing guitar. Name another contemporary action film with something like that in it.

These are all things that are going to come up anyway, but they're not what I want to focus on here. I want to look at the film's complex conceptualization of masculinity. After all, it does ask us, "who killed the world?"

More after the jump.

If you've seen the film or read anything about it, you're probably already aware that the film has earned a reputation for its feminist treatment of the story. Furiosa's goal is to find a feminine paradise far away from the rule of men who treat her and the other women as objects, their sole purpose being production. The society at the Citadel is hopelessly patriarchal, one that privileges the positions of men even as those in power are slowly destroying those who are not. Yes, in addition to creating a film about confronting the patriarchy, Miller also touches on issues of class warfare, as well as environmental responsibility. He's the Bernie Sanders of action directors.

But what's really fascinating about Miller's treatment of these big concepts is how he ties them all back to masculinity (intersectionality at work in a Hollywood blockbuster; tell me you ever thought you'd see those words in that order). Shortly after the film came out, Arthur Chu at The Daily Beast wrote a terrific article titled "'Mad Max:' How Men's Rights Activists Killed the World," in which he goes into great detail about how the Mad Max films have always been condemnations of toxic masculinity. That is to say, the kind of macho, hyper-masculinity that claims that men are inherently superior to women, and that it's a man's job to fight who he wants to fight (and often), fuck who he wants to fuck (again, often, as long as its a woman), and have the world handed to them because of that Y-chromosome. This is, essentially, bro-culture, created from equal parts entitlement and violence. Chu posits that the Mad Max films place the blame for the world's end on this phenomenon, and that, if left unchecked, toxic masculinity will lead to something apocalyptic in our culture.

This is certainly true of Fury Road, but what's fascinating is that Miller takes care to create a very nuanced portrayal of masculinity in the film. This isn't the "kill-all-the-men" form of feminism that the deplorable men's rights activists are claiming the film is supporting (also: that form of feminism isn't real), but rather a study in the different strands of masculinity, with Max, Nux, and Immorten Joe representing three different approaches.

First, there's Max. As he intones in his opening voice-over, he's been bred through the tragedies of his life to have only a single instinct: survive. Max is a loner, but he's a loner through his own actions. The ghosts of those who died because he couldn't save them continue to haunt him throughout the film, particularly a young girl who recurs in his visions. In the first Mad Max film (1979), Max wanted to quit his job as a "road warrior" because he felt that he was enjoying the violence. As a result, he lost everything he had. Max never fully embodied the idea of toxic masculinity, but he was enough of a participant to have it plague his life. At the beginning of Fury Road, he's completely alone because it's the only way he's going to survive. He can neither commit or be a victim of acts of violence if he has no one around.

In a way, Max is aware of the dangers of his masculinity, but is powerless to change it. Try as he might, he will always contribute to the problem through his participation. That's what makes it so fascinating that, for nearly the first hour of the film, he's chained to the front of Nux's vehicle, a glorified hood ornament for an instrument of death. In fact, Miller delightfully subverts action movie norms by making the title character essentially second-banana to Furiosa. This isn't his story, and Max wisely keeps to the side, playing a supportive role in Furiosa's plans rather than hijacking it as his own.

Max comes to represent an enlightened form of masculinity. He's willing to help Furiosa achieve of goals of sanctuary, but when she's been embraced by the people of the Citadel for her role in Immorten Joe's death, he slips away in the crowd. There's no place for him in Furiosa's feminine oasis; he'll only invite further trouble, and the cycle of violence and destruction will begin anew.

Nux, on the other hand, represents a transformed masculinity. He begins the film as a war boy, fully embracing the idea of dying in combat being the way into immortal paradise. He is toxic masculinity personified: bloodlust and a glorified concept of violence, coupled with the belief that only bloodshed can solve any problem. The war boys are also indoctrinated with the belief that the mechanical is holy; Nux describes several things that he perceives to be beautiful as chrome, and the war boys spray silver spray paint onto their faces just before sacrificing their lives in battle. Hell, there's even a brief scene in which the war boys grab the steering wheels for there vehicles from what's essentially an alter; what's more traditionally masculine than worshipping cars?

But over the course of the journey, Nux is humbled by his experiences with the women, even developing feelings for Capable (Riley Keough). Through these encounters and interactions Nux is able to cast aside the toxic masculinity that has consumed him and assist Furiosa in her quest alongside Max. However, as with Max, he cannot completely shake the consequences of his prior actions. He is, after all, still seen as a war boy, and therefore as an avatar of toxic masculinity. He cannot return to the Citadel, because he, too, cannot fully rescind who he is. His contribution has to be a sacrifice: he takes his own life in an effort to block the chase, allowing Furiosa and the others to escape back to the Citadel without any further troubles.

So that leaves Immorten Joe, the symbol of unrepentant male privilege. Joe has established himself as a warlord through controlling the water supply, and he takes great joy in his ability to tease his followers and use his women to his own ends. Joe is the horrifying face of toxic masculinity; it's no surprise that his emblem appears on his body as a belt buckle, placed squarely over his crotch as a symbol of phallic superiority, as well as etched into the cliff in which he resides.

Miller has obviously positioned him as the villain, of course, which underscores the underlying theme of destructive masculinity. But what's fascinating is that Joe and the war boys are also presented as physically deformed. The war boys have tumors protruding from their bodies, their illnesses necessitating the need for "blood bags" in order to stay alive. And Joe himself is a ghastly figure, his body covered in pustules and skin that's stretched from prolonged exposure to extreme elements. The metaphor here is clear: the bloodlust and animalistic nature of these people have eroded their bodies, leaving them disfigured and scarred. Their toxic masculinity is causing them to devolve.

It's no surprise that eventually this attitude would be challenged by someone in Joe's keep. When Furiosa sneaks the women out in a rig during a supply run, Joe is alerted to the problem when he spies her rig going off-course. He immediately runs to the vault in which he kept his breeders, only to find the space empty, with the phrases "our babies will not be warlords" and "who killed the world" etched on the floor and wall. And looking down into the next room, he sees what is my choice for "best shot:"

*Best Shot*

Miller has made his subtext text in this image. A stunning composition in its own right, a woman with a shotgun pointed squarely at the warlord, the phrase "we are not things" scrawled on the wall behind her. It's the film's ultimate mission statement: the women have usurped the patriarchy, and have created a space in the world in which they will no longer be things. As the different-yet-related examples of Max, Nux, and Immorten Joe demonstrate, Miller has crafted an examination of masculinity that condemns hyper-violent privilege but offers no easy suggestions for how to purge it from the world. Creating Furiosa's feminine utopia means starting over without the influence of toxic masculinity. The fate of the war boys and war pups (young children) still in the Citadel remains unknown. Nux and Immorten Joe had to die. And Max, once again, must venture off alone, his only instinct being survival.

Comments